The Port of Hammamet (La Scala) Between Archives, Memory, and History

Hammamet in the 19th Century: A Town Turned Toward the Sea

In the 19th century, Hammamet was a small but active coastal town whose life revolved largely around the sea. Its inhabitants lived from fishing, small-scale agriculture, especially citrus, olives, and gardens fed by local springs, and maritime trade with nearby coastal cities. Boats connected Hammamet to Tunis, Sousse, and other Mediterranean shores, transporting food, textiles, oil, and local products.

Table Of Content

- Hammamet in the 19th Century: A Town Turned Toward the Sea

- A Port Officially Attested Since the 19th Century

- From Commercial Port to Secondary Port Under the Protectorate

- The Second World War: An Exposed but Poorly Documented Site

- La Scala: Between Destruction, Erosion, and Local Memory

- Photo Gallery

The town’s position along the Gulf of Hammamet made it naturally open to exchange. In a period when land transport was slow and difficult, a port was not a luxury but a necessity. It allowed merchants to export agricultural goods, fishermen to sell their catch beyond the local market, and the town to remain economically connected to the wider region. The sea was both a source of livelihood and a gateway to prosperity, which explains why the existence of an organised port in Hammamet was so important for its development.

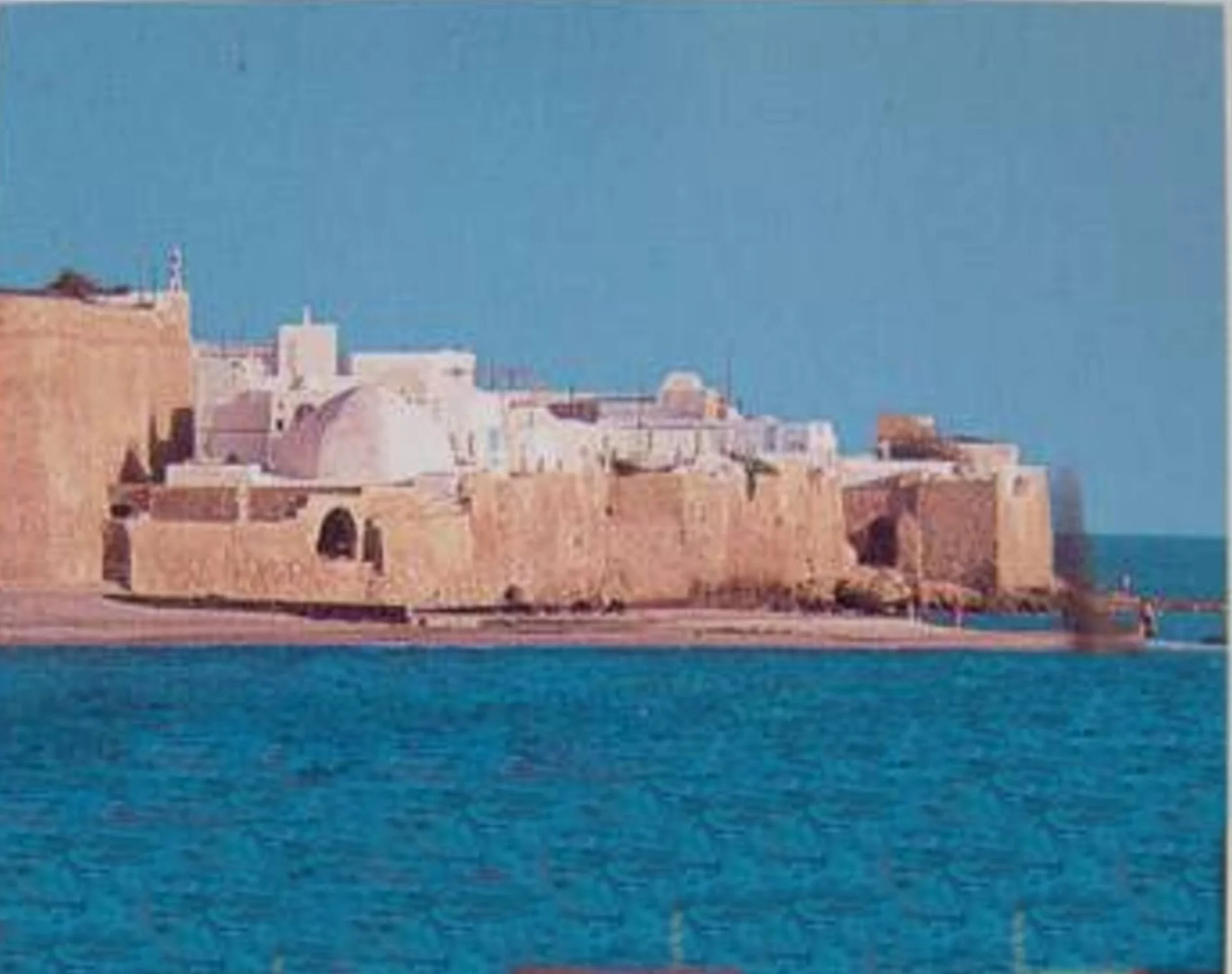

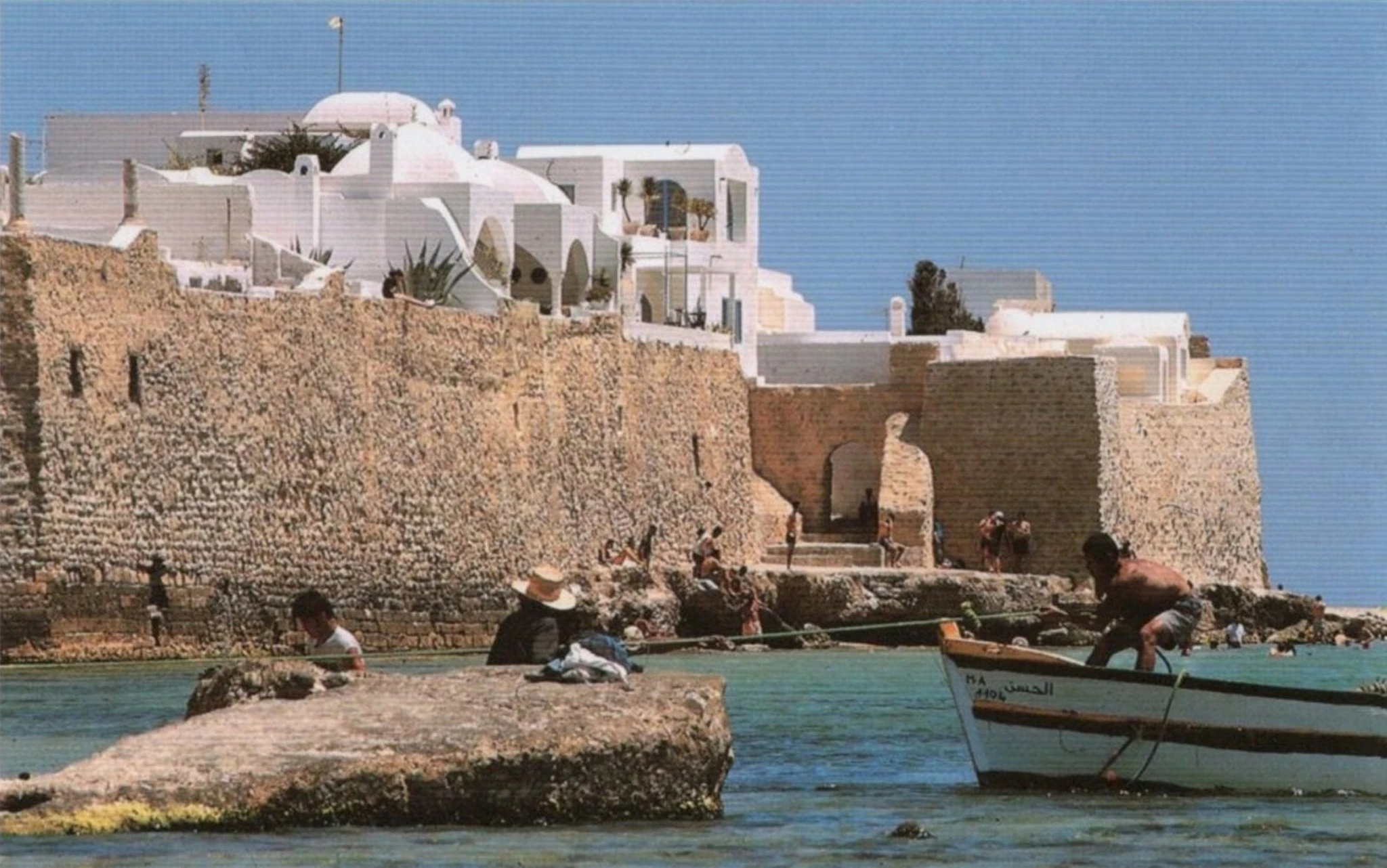

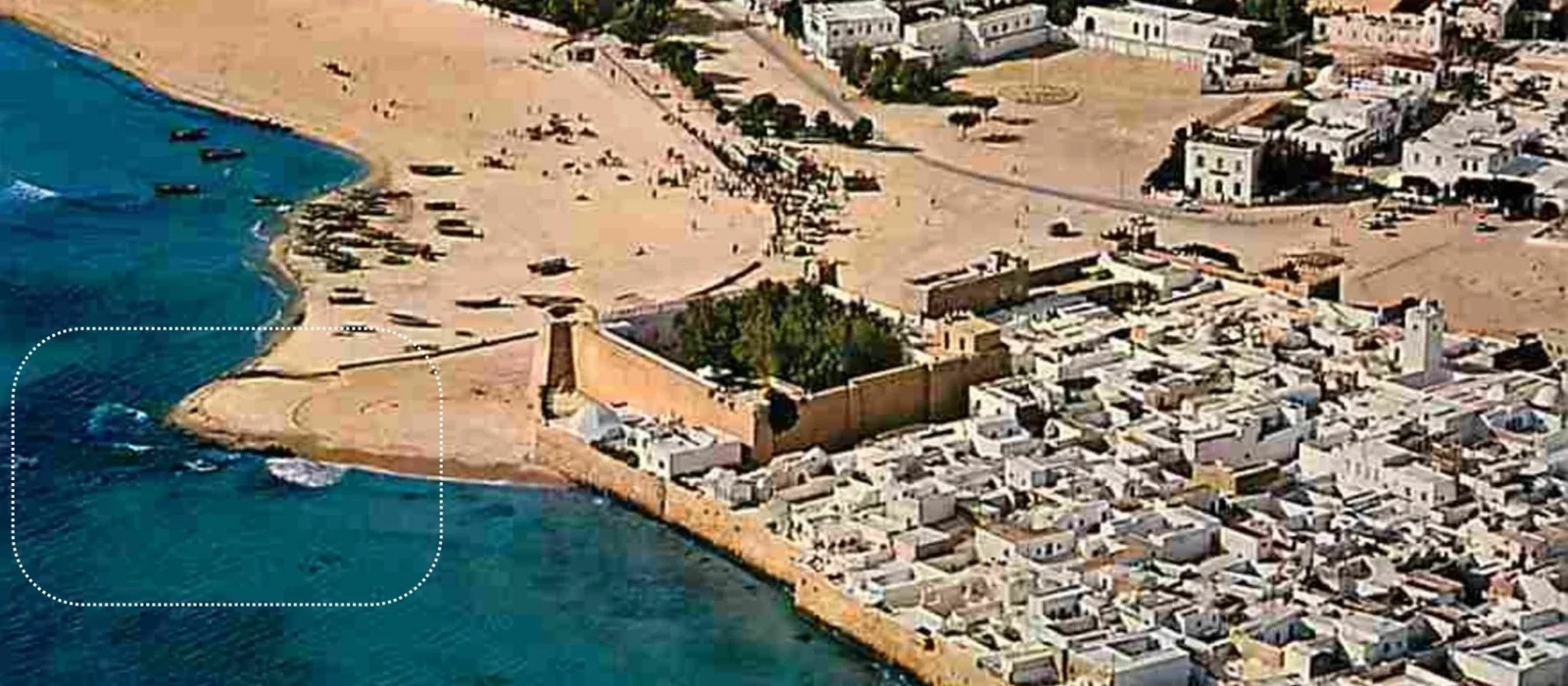

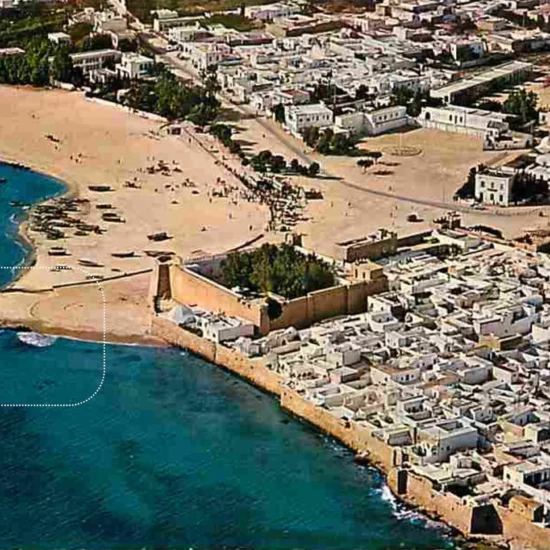

Historical research and archival documents now make it possible to better understand the existence and development of an old port in Hammamet, locally known as La Scala, or Esqala, whose remains are still visible in the town centre today in the form of rocks and wave-beaten structures.

A Port Officially Attested Since the 19th Century

An archival document dated 19 Dhul Hijjah 1289 AH, 1872, preserved in the National Archives, formally confirms that Hammamet had a port officially recognized by the Tunisian state before the French colonial period.

By beylical decree, the ruler of Tunisia decided in 1872 to convert the port of Hammamet into a commercial port, mainly intended for the export of goods, following the model of the port of La Marsa. This decision was transmitted by Mustapha Ben Ismaïl, governor of Cap Bon, to General Khaïreddine, then serving as minister.

The same document specifies that the port administration was structured as follows. Ahmed Ben Mohamed Kababou, a notary, was responsible for registering goods. Ali Ben Othman El Karoui El Hanafi was responsible for supervising exports. Both were appointed following written recommendations from the notables of Hammamet.

This text clearly confirms the existence of a functional, organized, and active port in Hammamet in the 19th century, well before the French colonization in 1881.

From Commercial Port to Secondary Port Under the Protectorate

With the establishment of the French Protectorate in 1881, port policy shifted toward major strategic ports such as Tunis, Bizerte, and Sfax.

Hammamet, although previously equipped with a recognised port, gradually lost its major commercial role and retained mainly a local function, likely focused on fishing and coastal trade.

It was in this context that the kasbah, the fort of Hammamet, became a key point of military and administrative control, particularly under the authority of French officers, including Commander Bodier, who was responsible for local security on behalf of France.

The Second World War: An Exposed but Poorly Documented Site

During the Tunisian Campaign from 1942 to 1943, Hammamet gained strategic importance. The town hosted German headquarters, including that of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel. Axis forces were present for about six months before retreating and being defeated by the Allies in spring 1943.

However, unlike major ports such as Bizerte or Tunis, no international military source explicitly mentions a documented bombing of the port of Hammamet.

This explains the absence of precise references in Allied or German military archives concerning the destruction of a port named Scala.

La Scala: Between Destruction, Erosion, and Local Memory

The remains visible today, aligned rocks and shapes resembling jetties or quays, most likely correspond to the remains of the 19th century commercial port documented in the 1872 archives, or to older port structures modified over time, or to cumulative damage caused by marine erosion, the gradual abandonment of the site, and possibly undocumented local military actions during the Second World War.

Local oral memory, passed down through generations, speaks of a port bombed during the war. This is consistent with the intense military context in the Gulf of Hammamet, even if international written sources remain silent about a specific bombing.

Comparing the 1872 archival text with recent historical research leads to a solid conclusion. Yes, Hammamet had a real, official port, recognised by beylical decree and used for export as early as the 19th century.

This port gradually declined under the French Protectorate, becoming a secondary port.

During the Second World War, Hammamet was a strategic site occupied by German forces, making coastal damage plausible.

Today’s Scala most likely represents the remains of this ancient port, transformed by time, history, and the sea. In short, La Scala is neither a myth nor a simple rock formation, but a real historical site, at the crossroads of official archives, military history, and the living memory of Hammamet’s inhabitants.

Photo Gallery

Extremely motivated to constantly develop my skills and grow professionally. I try to build my knowledge, flexibility, and interpersonal skills through several projects and within different teams.

No Comment! Be the first one.